He was a champion of freedom, who spent one-third of his life in a prison cell; a revolutionary who espoused armed conflict against the state, yet became a global icon of peace and moral virtue.

Nelson Mandela, the first black president of South Africa, died on Thursday at the age of 95. Archbishop Desmond Tutu called him “one of the greatest human beings to walk this Earth.”

Certainly he was a giant of the 20th century, an extraordinary leader who — like Winston Churchill, Mahatma Gandhi and Pope John Paul II — confronted the oppressors of his time and, against enormous odds, changed the course of history.

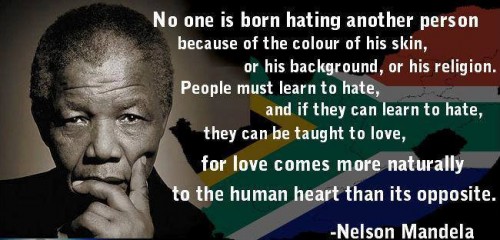

Although best known for skilfully leading South Africa out of the violence and racial hatred of apartheid, Mandela’s greatest legacy is the magnanimity and moral purpose he constantly demonstrated to the world.

In 1990, he emerged after 27 years behind the walls of the apartheid regime’s toughest prisons advocating not anger and revenge, but reconciliation and forgiveness. After winning South Africa’s first democratic election, he invited the lawyer who had prosecuted him decades before, along with many of his former white jailers, to attend his presidential inauguration as VIP guests.

Five years later, in one of his greatest moral acts, he simply relinquished the reins of high office — a breathtaking symbolic move in a continent beset by power-hungry tyrants and dictators.

“He was never in politics for power or money. He had too much integrity for that,” says Lucie Page, a Montreal writer and filmmaker who came to know Mandela well through her husband, Jay Naidoo, a former anti-apartheid activist who served in Mandela’s cabinet.

“Why was he so different from other African leaders? Because he put values first, not power,” says Page. “And he practised what he preached.”

Everywhere the powerful and the famous — presidents, prime ministers and the world’s biggest celebrities — longed to be seen at Mandela’s side, to bask in the magic glow of a true international superstar.

Muhammad Ali said he was “awestruck” when he met Mandela, or “Madiba,” as he was affectionately known.

But ordinary people were drawn to him too, from all corners of the planet, a fact that amazed Mandela himself.

In 1990, at the end of his first trip to Canada, only months after leaving prison, his airplane stopped briefly to refuel in Goose Bay, Labrador, before crossing the Atlantic. As Mandela strolled on the tarmac, he was surprised to see a small crowd of cheering Innu teenagers who had come to the airport after hearing that Mandela’s plane might be stopping there.

“In talking with these bright young people,” Mandela wrote in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, “I learned that they had watched my release on television and were familiar with events in South Africa. ‘Viva ANC!’ one of them said.”

With his huge grin and piercing eyes, Mandela had a particular genius for connecting with people, in making you feel special, says Page.

“You could cut his charisma with a knife. Before you even saw him, you would feel his presence. Don’t ask me to explain it,” she says. “He had an energy, an aura. I’ve met lots of kings and presidents, but no one is like Mandela. When you were together he made you feel like the centre of his world.”

Mandela also had a soft spot for Canada. He loved to receive gifts of maple syrup, says Page. More importantly, he never forgot the forceful role Canadians played — both through the government of Brian Mulroney and the work of civil society groups — in pushing the Commonwealth to impose economic sanctions on South Africa in the 1980s.

“We regard you as one of our great friends because of the solid support we have received from you and Canada over the years,” Mandela told Mulroney in a phone call the day after his release from prison.

Four months later, Mandela spoke from the floor of the House of Commons in Ottawa — the first private, non-official foreign citizen invited to address the Canadian Parliament in 40 years. In his thickly articulated African accent, he thanked Canadians for having “reached out across the seas . . . to the rebels, the fugitives and the prisoners” of the apartheid regime.

Mandela was born on July 18, 1918 in a small rural village of mud-and-grass huts in the Transkei, a mystical region of high, lonely plateaus and fertile river valleys on the Indian Ocean coast. His father, a local Xhosa chief, named his new son Rolihlahla, which loosely translates into “troublemaker.”

Mandela was well educated at local mission schools, where a Wesleyan teacher, unable to pronounce his Xhosa name, called him Nelson instead.

At 23 Mandela fled his rural life for the bright lights of Johannesburg, where he was befriended by Walter Sisulu, a young businessman and political activist with the African National Congress. While working as a clerk in a local law firm, Mandela enrolled as one of only a handful of black students at the University of Witwatersrand. By the 1950s he was a qualified attorney and co-founder, with Oliver Tambo — who would later lead the ANC-in-exile during Mandela’s decades in prison — of the first black law firm in Johannesburg.

South Africa was changing: the Afrikaner National Party had come came to power in the 1950s advocating a policy of rigid racial segregation. As life became more difficult for non-white citizens, Mandela’s practice thrived, and he gained a measure of fame as a gifted litigator, and a dashing young figure inside the increasingly militant ANC.

Mandela could have enjoyed a relatively comfortable, lucrative life as a successful black lawyer, even in South Africa. But he gave it up to campaign openly against the apartheid laws. By 1961 black protesters were being shot by police, the ANC had been outlawed, and Mandela went underground, continuing his activism from the shadows, and acquiring a mythic stature as “The Black Pimpernel.”

He persuaded the ANC to put aside its long-standing policy of non-violence and launch an armed insurrection against the government. With Sisulu he created the ANC guerrilla wing Unkhonto we Sizwe (the Spear of the Nation), and organized a series of bomb explosions at power plants and government offices around South Africa.

In 1962 he was tracked down and arrested for treason. The lengthy trial became an international sensation, prompting calls for leniency from Moscow to Washington. Two years later, Mandela, Sisulu, and seven other ANC defendants were found guilty of trying to overthrow the government and all — expecting the gallows — were sentenced to life in prison.

“You chaps won’t be in prison long,” Mandela recalls a prison warder telling him the night after the trial. “The demand for your release is too strong. After a year or two, you will get out and you will return as national heroes. Crowds will cheer you, everyone will want to be your friend, women will want you. Ah, you chaps have it made.”

It was a good prediction, but the time frame was off by nearly three decades. Mandela and his brothers-in-arms spent the next 18 years in one of the world’s most forbidding gulags — a windswept, rocky outpost called Robben Island, seven kilometres south of Cape Town. Mandela’s cell was so small that when he lay down to sleep — there was no bed, only a blanket and a grass mat on a concrete floor — his head touched one wall and his feet the other.

It was a crushing existence without respite from loneliness or hard labour, but Mandela used the time to continue the fight against the government, organizing his fellow prisoners and slowly winning greater privileges from their jailers. In the mini-politics of Robben Island — where there were disputes among ANC prisoners about everything from prison matters to larger strategic questions about the anti-apartheid struggle — Mandela honed his political and negotiating skills, and his famed ability to listen.

Although feared by many whites as a Communist ideologue, Mandela was in fact a shrewd pragmatist and a democrat — qualities the Afrikaner government gradually became aware of after it opened secret talks with Mandela in 1986. Four years earlier Mandela had been transferred to more comfortable conditions at Pollsmoor Prison on the mainland, and it was there — and later a private cottage on the grounds of Victor Verster Prison in Cape Town — that Mandela and senior white government leaders carried out years of informal, clandestine talks that culminated in Mandela’s release in 1990.

One of those encounters was a face-to-face meeting with South African president P.W. Botha, known as the “Great Crocodile.” As Mandela was standing outside Botha’s office waiting to enter, Niel Barnard, head of the National Intelligence Service, noticed that his shoelaces weren’t properly tied. Prison officials had outfitted Mandela with a business suit for the meeting, but he had been behind bars so long without proper shoes and laces that he’d forgotten how to tie them.

Seconds before the door to the president’s office opened, Barnard — one of South Africa’s highest-ranking officials — knelt down at the feet of the world’s most famous prisoner, to tie his shoes.

Mandela may have been famous, but after a quarter-century in captivity, few people knew what he actually looked like, or how much he had aged, a fact that made it relatively easy for prison officials to take Mandela on a series of casual drives around Cape Town, to acclimatize him to the outside world in the years leading up to his actual release. Mandela recalled sitting in the back seat of a car — “absolutely riveted” as he watched the “ordinary activities of people out in the world” — while a senior prison official showed him around the city.

On one such outing his driver and escort, Col. Gawie Marx, the deputy commander of Pollsmoor Prison, left Mandela alone in the car while he went into a store to buy cold drinks for them both. “For the first time in 22 years I was out in the world and unguarded,” Mandela wrote.

“I had a vision of opening the door, jumping out, and then running and running until I was out of sight . . . but then I took control of myself; such an action would be unwise and irresponsible, not to mention dangerous.

“I was greatly relieved a few moments later when I saw the colonel walking back to the car with two cans of Coca-Cola.”

In 1989 Botha was succeeded as president by F.W. de Klerk, and a year later, beset by international sanctions and increasing domestic violence — and encouraged by the tone of its secret negotiations with Mandela — the government lifted the ban on the ANC and its sister organizations, and freed Mandela, Sisulu and dozens of other political prisoners.

Mandela’s stunning walk through the gates of Victor Verster Prison, hand-in-hand with his wife Winnie, was watched by millions around the planet. At 24 Sussex Drive in Ottawa, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney sat glued to the TV with his four-year-old son Nicolas.

“A great man is leaving prison,” Mulroney told his son, according to his memoirs. “I want you to watch it and I want you to remember it.”

Mandela’s release came three months after the fall of the Berlin Wall, amid a profound sense of change, hope and global optimism.

“We had the feeling that history was really moving, we were moving away from all the lies and ideologies of the postwar period,” says Jean-Francois Lepine, the Radio-Canada journalist who covered Mandela’s first weeks of freedom. “A fundamental change was taking place in the world, and Mandela was part of that.”

Despite the joy of 1990, South Africa was on fire, with rising violence and killings among both blacks and whites as rival groups jockeyed for position in a new political future. Amid the turmoil, over the next four years Mandela and de Klerk crafted a new, democratic constitution, considered one of the most progressive human-rights documents in the world. Together they were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, before leading their followers through peaceful elections, avoiding the bloodbath that so many observers had feared.

“Never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another,” said Mandela at his presidential inauguration in 1994. “The sun shall never set on so glorious a human achievement.”

In power, Mandela healed a wounded nation by creating the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a model for the world, aimed at resolving the horrors of apartheid not through retribution, but by seeking truth for its victims, and amnesty for perpetrators willing to disclose their political crimes.

Out of power, after handing the presidency to Thabo Mbeki in 1999, Mandela confronted Mbeki’s public denials about the AIDS crisis — a taboo subject in much of Africa — by announcing that AIDS had taken the life of his adult son Makgatho.

Amid the great hardships that Mandela faced, none matched the sorrows of his private life, including the death of his son. His first two marriages, to Evelyn Mase and Winnie Madikizela, ended in divorce. (In 1998 he married for a third time, to Graca Michel, the widow of former Mozambican president Samora Michel.) He was also denied, during his long years in prison, the company and pleasure of his family, including his five children. And so great were public demands for his time and attention after his release that again, he and his family suffered.

“He loves kids,” says Lucie Page. “He told me he only regrets one thing: he was a father to a nation, but he regrets not being able to be a father to his own children. I know that weighed heavily on him.”

Almost certainly he was also troubled by the state of his country in recent years. Although South Africa’s economy is prosperous, the gaps between its rich and poor remain vast, and its government is seen as increasingly divided and corrupt — perhaps partly the fault of Mandela himself, who disappointed many, before and after his retirement, for failing to admonish political allies, or speak out against corruption.

“His one weakness has been his unshakable loyalty to his comrades, so that he allowed poorly performing ministers to continue in his cabinet,” Desmond Tutu once said.

Still, his heroic achievements easily eclipsed his failures. Mandela, said Tutu, had the “remarkable gift of making South Africans feel good about ourselves.” He inspired millions, and transformed his country from a “pariah state, a repulsive caterpillar . . . into a gorgeous butterfly.”

Five years later, in one of his greatest moral acts, he simply relinquished the reins of high office — a breathtaking symbolic move in a continent beset by power-hungry tyrants and dictators.

“He was never in politics for power or money. He had too much integrity for that,” says Lucie Page, a Montreal writer and filmmaker who came to know Mandela well through her husband, Jay Naidoo, a former anti-apartheid activist who served in Mandela’s cabinet.

“Why was he so different from other African leaders? Because he put values first, not power,” says Page. “And he practised what he preached.”

Everywhere the powerful and the famous — presidents, prime ministers and the world’s biggest celebrities — longed to be seen at Mandela’s side, to bask in the magic glow of a true international superstar.

Muhammad Ali said he was “awestruck” when he met Mandela, or “Madiba,” as he was affectionately known.

But ordinary people were drawn to him too, from all corners of the planet, a fact that amazed Mandela himself.

In 1990, at the end of his first trip to Canada, only months after leaving prison, his airplane stopped briefly to refuel in Goose Bay, Labrador, before crossing the Atlantic. As Mandela strolled on the tarmac, he was surprised to see a small crowd of cheering Innu teenagers who had come to the airport after hearing that Mandela’s plane might be stopping there.

“In talking with these bright young people,” Mandela wrote in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, “I learned that they had watched my release on television and were familiar with events in South Africa. ‘Viva ANC!’ one of them said.”

With his huge grin and piercing eyes, Mandela had a particular genius for connecting with people, in making you feel special, says Page.

“You could cut his charisma with a knife. Before you even saw him, you would feel his presence. Don’t ask me to explain it,” she says. “He had an energy, an aura. I’ve met lots of kings and presidents, but no one is like Mandela. When you were together he made you feel like the centre of his world.”

Mandela also had a soft spot for Canada. He loved to receive gifts of maple syrup, says Page. More importantly, he never forgot the forceful role Canadians played — both through the government of Brian Mulroney and the work of civil society groups — in pushing the Commonwealth to impose economic sanctions on South Africa in the 1980s.

“We regard you as one of our great friends because of the solid support we have received from you and Canada over the years,” Mandela told Mulroney in a phone call the day after his release from prison.

Four months later, Mandela spoke from the floor of the House of Commons in Ottawa — the first private, non-official foreign citizen invited to address the Canadian Parliament in 40 years. In his thickly articulated African accent, he thanked Canadians for having “reached out across the seas . . . to the rebels, the fugitives and the prisoners” of the apartheid regime.

Mandela was born on July 18, 1918 in a small rural village of mud-and-grass huts in the Transkei, a mystical region of high, lonely plateaus and fertile river valleys on the Indian Ocean coast. His father, a local Xhosa chief, named his new son Rolihlahla, which loosely translates into “troublemaker.”

Mandela was well educated at local mission schools, where a Wesleyan teacher, unable to pronounce his Xhosa name, called him Nelson instead.

At 23 Mandela fled his rural life for the bright lights of Johannesburg, where he was befriended by Walter Sisulu, a young businessman and political activist with the African National Congress. While working as a clerk in a local law firm, Mandela enrolled as one of only a handful of black students at the University of Witwatersrand. By the 1950s he was a qualified attorney and co-founder, with Oliver Tambo — who would later lead the ANC-in-exile during Mandela’s decades in prison — of the first black law firm in Johannesburg.

South Africa was changing: the Afrikaner National Party had come came to power in the 1950s advocating a policy of rigid racial segregation. As life became more difficult for non-white citizens, Mandela’s practice thrived, and he gained a measure of fame as a gifted litigator, and a dashing young figure inside the increasingly militant ANC.

Mandela could have enjoyed a relatively comfortable, lucrative life as a successful black lawyer, even in South Africa. But he gave it up to campaign openly against the apartheid laws. By 1961 black protesters were being shot by police, the ANC had been outlawed, and Mandela went underground, continuing his activism from the shadows, and acquiring a mythic stature as “The Black Pimpernel.”

He persuaded the ANC to put aside its long-standing policy of non-violence and launch an armed insurrection against the government. With Sisulu he created the ANC guerrilla wing Unkhonto we Sizwe (the Spear of the Nation), and organized a series of bomb explosions at power plants and government offices around South Africa.

In 1962 he was tracked down and arrested for treason. The lengthy trial became an international sensation, prompting calls for leniency from Moscow to Washington. Two years later, Mandela, Sisulu, and seven other ANC defendants were found guilty of trying to overthrow the government and all — expecting the gallows — were sentenced to life in prison.

“You chaps won’t be in prison long,” Mandela recalls a prison warder telling him the night after the trial. “The demand for your release is too strong. After a year or two, you will get out and you will return as national heroes. Crowds will cheer you, everyone will want to be your friend, women will want you. Ah, you chaps have it made.”

It was a good prediction, but the time frame was off by nearly three decades. Mandela and his brothers-in-arms spent the next 18 years in one of the world’s most forbidding gulags — a windswept, rocky outpost called Robben Island, seven kilometres south of Cape Town. Mandela’s cell was so small that when he lay down to sleep — there was no bed, only a blanket and a grass mat on a concrete floor — his head touched one wall and his feet the other.

It was a crushing existence without respite from loneliness or hard labour, but Mandela used the time to continue the fight against the government, organizing his fellow prisoners and slowly winning greater privileges from their jailers. In the mini-politics of Robben Island — where there were disputes among ANC prisoners about everything from prison matters to larger strategic questions about the anti-apartheid struggle — Mandela honed his political and negotiating skills, and his famed ability to listen.

Although feared by many whites as a Communist ideologue, Mandela was in fact a shrewd pragmatist and a democrat — qualities the Afrikaner government gradually became aware of after it opened secret talks with Mandela in 1986. Four years earlier Mandela had been transferred to more comfortable conditions at Pollsmoor Prison on the mainland, and it was there — and later a private cottage on the grounds of Victor Verster Prison in Cape Town — that Mandela and senior white government leaders carried out years of informal, clandestine talks that culminated in Mandela’s release in 1990.

One of those encounters was a face-to-face meeting with South African president P.W. Botha, known as the “Great Crocodile.” As Mandela was standing outside Botha’s office waiting to enter, Niel Barnard, head of the National Intelligence Service, noticed that his shoelaces weren’t properly tied. Prison officials had outfitted Mandela with a business suit for the meeting, but he had been behind bars so long without proper shoes and laces that he’d forgotten how to tie them.

Seconds before the door to the president’s office opened, Barnard — one of South Africa’s highest-ranking officials — knelt down at the feet of the world’s most famous prisoner, to tie his shoes.

Mandela may have been famous, but after a quarter-century in captivity, few people knew what he actually looked like, or how much he had aged, a fact that made it relatively easy for prison officials to take Mandela on a series of casual drives around Cape Town, to acclimatize him to the outside world in the years leading up to his actual release. Mandela recalled sitting in the back seat of a car — “absolutely riveted” as he watched the “ordinary activities of people out in the world” — while a senior prison official showed him around the city.

On one such outing his driver and escort, Col. Gawie Marx, the deputy commander of Pollsmoor Prison, left Mandela alone in the car while he went into a store to buy cold drinks for them both. “For the first time in 22 years I was out in the world and unguarded,” Mandela wrote.

“I had a vision of opening the door, jumping out, and then running and running until I was out of sight . . . but then I took control of myself; such an action would be unwise and irresponsible, not to mention dangerous.

“I was greatly relieved a few moments later when I saw the colonel walking back to the car with two cans of Coca-Cola.”

In 1989 Botha was succeeded as president by F.W. de Klerk, and a year later, beset by international sanctions and increasing domestic violence — and encouraged by the tone of its secret negotiations with Mandela — the government lifted the ban on the ANC and its sister organizations, and freed Mandela, Sisulu and dozens of other political prisoners.

Mandela’s stunning walk through the gates of Victor Verster Prison, hand-in-hand with his wife Winnie, was watched by millions around the planet. At 24 Sussex Drive in Ottawa, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney sat glued to the TV with his four-year-old son Nicolas.

“A great man is leaving prison,” Mulroney told his son, according to his memoirs. “I want you to watch it and I want you to remember it.”

Mandela’s release came three months after the fall of the Berlin Wall, amid a profound sense of change, hope and global optimism.

“We had the feeling that history was really moving, we were moving away from all the lies and ideologies of the postwar period,” says Jean-Francois Lepine, the Radio-Canada journalist who covered Mandela’s first weeks of freedom. “A fundamental change was taking place in the world, and Mandela was part of that.”

Despite the joy of 1990, South Africa was on fire, with rising violence and killings among both blacks and whites as rival groups jockeyed for position in a new political future. Amid the turmoil, over the next four years Mandela and de Klerk crafted a new, democratic constitution, considered one of the most progressive human-rights documents in the world. Together they were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, before leading their followers through peaceful elections, avoiding the bloodbath that so many observers had feared.

“Never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another,” said Mandela at his presidential inauguration in 1994. “The sun shall never set on so glorious a human achievement.”

In power, Mandela healed a wounded nation by creating the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, a model for the world, aimed at resolving the horrors of apartheid not through retribution, but by seeking truth for its victims, and amnesty for perpetrators willing to disclose their political crimes.

Out of power, after handing the presidency to Thabo Mbeki in 1999, Mandela confronted Mbeki’s public denials about the AIDS crisis — a taboo subject in much of Africa — by announcing that AIDS had taken the life of his adult son Makgatho.

Amid the great hardships that Mandela faced, none matched the sorrows of his private life, including the death of his son. His first two marriages, to Evelyn Mase and Winnie Madikizela, ended in divorce. (In 1998 he married for a third time, to Graca Michel, the widow of former Mozambican president Samora Michel.) He was also denied, during his long years in prison, the company and pleasure of his family, including his five children. And so great were public demands for his time and attention after his release that again, he and his family suffered.

“He loves kids,” says Lucie Page. “He told me he only regrets one thing: he was a father to a nation, but he regrets not being able to be a father to his own children. I know that weighed heavily on him.”

Almost certainly he was also troubled by the state of his country in recent years. Although South Africa’s economy is prosperous, the gaps between its rich and poor remain vast, and its government is seen as increasingly divided and corrupt — perhaps partly the fault of Mandela himself, who disappointed many, before and after his retirement, for failing to admonish political allies, or speak out against corruption.

“His one weakness has been his unshakable loyalty to his comrades, so that he allowed poorly performing ministers to continue in his cabinet,” Desmond Tutu once said.

Still, his heroic achievements easily eclipsed his failures. Mandela, said Tutu, had the “remarkable gift of making South Africans feel good about ourselves.” He inspired millions, and transformed his country from a “pariah state, a repulsive caterpillar . . . into a gorgeous butterfly.”