This is really interesting so read on people. Chickens and dinosaurs…what do they have in common. Scientists from the University of Chile, the University of Chicago and the University of Illinois at Chicago created the prosthetic tail. They studied chickens because they are distant descendants of T.Rex and the study reveals that the chickens with tails seemed to walk with more of a hip-driven movement, suggesting that perhaps therapod dinosaurs did too.

Tyrannosaurus Rex might be one of the best known dinosaurs, but scientists are still not exactly sure how the prehistoric giant walked.

And in a bid to find out, a group of researchers attached fake tails to chickens and analysed the way they walked.

While the idea might look more like a school project than a serious experiment, the scientists chose chickens because modern birds descend from a group of dinosaurs that includes the T-Rex.

Scientists from the University of Chile, the University of Chicago and the University of Illinois at Chicago created prosthetic tails to simulate how a seven tonne T-Rex, which measured over 40ft long, would have walked.

The fearsome dinosaur roamed the earth in the Late Cretaceous, around 66million years ago.

HOW DID THE TYRANNOSAUR REX WALK?

The new study suggests that the fearsome dinosaur’s walk was hip driven.

T-Rex lived during the Late Cretaceous period – 66million years ago.

While most people think the carnivorous dinosaur stood upright, it had a bird-like posture and kept its tail in the air and its head pitched forward.

Its massive skull was balanced by its heavy tail, which was around 15 per cent of its body mass.

The creature would have changed direction slowly because if its massive inertia but was agile enough to run.

T-Rex had a top speed of 25mph (40kmp) which is a little slower than a horse.

The dinosaur belonged to the theropod group of dinosaurs, which also included the foot-long Anchiornis huxleyi, all of which are very distantly related to birds today.

They conducted the bizarre experiment to study the way the dinosaur’s descendent moves with the addition of a long and relatively heavy tail, which is actually a wooden stick with modelling clay that four chickens have worn from birth.

The scientists were careful to keep the tails at 15 per cent of the birds’ body weight, so they had to continuously replace them while they were growing, IBTimes reported.

They chose the weight because they think the proportion is similar to the weight of a theropod dinosaur’s tail, compared to its body.

The researchers discovered that the chickens raised with the tails walked in a different way to those without them.

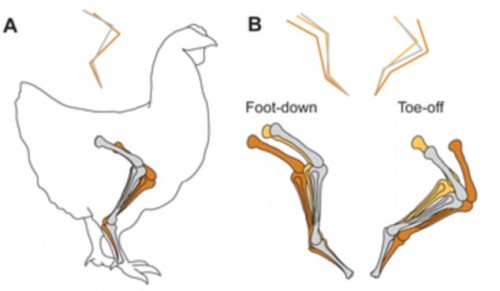

The birds with the prosthetic tails stood with their femurs – their upper leg bones – held more vertically and moved their knees differently when walking to the control birds, the study in the journal PLOS ONE revealed.

The birds with the prosthetic tails stood with their femurs – the upper leg bones – held more vertically and moved their knees differently when walking to the control birds, the study said. The control birds’ leg position is shown in grey and the chickens’ wearing the tails in orange

The study found that while the control birds moved from the knee, the chickens wearing the tails displayed a more hip-driven movement

‘These results indicate a shift from the standard bird, knee-driven bipedal locomotion to a more hip-driven locomotion, typical of crocodilians…mammals, and hypothetically, bipedal non-avian dinosaurs,’ the scientists wrote.

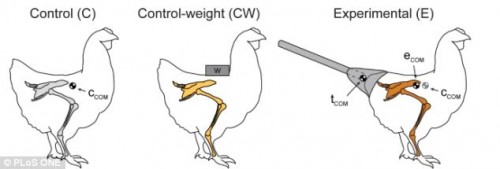

The scientists also raised a small brood of chickens wearing weighted coats to ensure that it wasn’t just the extra weight that caused the birds’ change of posture and way of walking.

But they found that the birds wearing the weighted coats close to the centre of their mass, walked similarly to the control chickens, indicating it was the tail that made the difference.

The scientists said: ‘Our experimental approach, although not perfect, was effective in displacing the [chickens’ centre of mass] and recreating locomotor patterns expected in non-avian theropods.

‘We expect that careful…manipulation of extant birds can open new avenues of experimental investigation into unexplored facets of dinosaur locomotor mechanics and energetics, providing a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between form and function in dinosaur evolution,’ they added.