The World War II era was a fertile time for the invention of new myths, forms of slang, folklore and legends. Some of these new ideas spread quickly from one culture to another and then entered the language of the world. The idea of gremlins -- small, troublemaking supernatural saboteurs -- sounds enough like a traditional folklore trope that one might assume it came from the Brothers Grimm or a Russian fairy tale. In truth, gremlin lore first emerged in the British Royal Air Force. As conceived in pilots' imaginations, they were unseen little sprites who got their jollies specifically by sabotaging aircraft.

During the war Walt Disney got word of a book being written by children's author Roald Dahl, then an RAF pilot. Disney thought that the mischievous little creatures -- who appeared to be more like fairies or leprechauns than trolls -- might make a good subject for an animated feature. Disney bought a controlling interest in Dahl's project before the book was completed. Thanks to some very successful PR, the legend of gremlins spread throughout the United States.

Dahl's book centers on an RAF pilot named Gus.When Gus crash-lands, he meets a gremlin who adopts his name and becomes Gremlin Gus. This opens the door to the world of the gremlins, sprites whose aircraft sabotage is explained as a defense of the grounds where their enchanted forest once stood. Female gremlins were called Fifinellas; genderless young gremlins were Widgets.

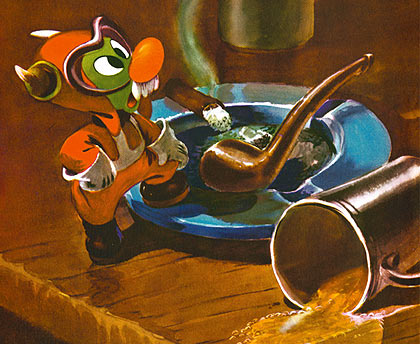

As Disney's planned feature film developed, its story was published in the December 1942 issue of Cosmopolitan. When Dahl's book followed the Cosmopolitan feature into print, the cover featured Disney's name in larger type than the author's. The look of the characters had been developed by Bill Justice, one of Disney's best animators. Justice also created most of the illustrations for the book.

Anticipating the release of its film in production, Disney made several attempts to establish a merchandising base for its gremlin characters, authorizing dolls, puppets and at least one puzzle. In addition, the Disney Gremlins were featured in a Look magazine Life Savers ad.

The next step was to bring the characters to comics. Western Publishing's first Disney gremlin tale, a dialogue-heavy six-page adaptation of Dahl's book, appeared in Dell's War Heroes #4 (April-June 1943), a non-Disney anthology title. From there, the Gremlins went on to a monthly two-page feature in Walt Disney's Comics and Stories. Initially drawn by Vivie Risto (WDC&S #33, June 1943), this series began as a talky, War Heroes-like Dahl adaptation; but one issue into the project, plans evidently changed. The new concept was to promote the single character of Gremlin Gus more than the film as a whole. This involved a new pantomime approach and a new artist, former Disney staffer Walt Kelly. Kelly produced a steady stream of dialogue-free stories with Gus and the Widgets from WDC&S #34 (1943) to #41 (1944). Kelly is better known today as the creator of the comic strip Pogo; nevertheless, his fans consider the Gremlin stories to be a high-water mark in his long career.

Unfortunately for Disney, their effort to promote gremlins was working too well; production of the feature film dragged, whereas advance publicity had created a fad that was already peaking. The public appeared to be going "gremlin-crazy" -- but too soon to benefit a film that might still be one or two years away.

In addition, there were ownership problems with the concept of gremlins. Though Disney could trademark individual characters like Gremlin Gus, they could not register the word "gremlin" or keep gremlins from being used by other creative content producers. Count Basie had recorded a song called "Dance of the Gremlins," and there was even a short-lived, non-Disney gremlin newspaper comic strip. When Warner Brothers made two cartoons featuring gremlins (both directed by Bob Clampett), Disney's animation department dropped the idea of finishing its feature film.

From some perspectives, this was for the best; Dahl was unhappy with much of the Disney gremlin material that he saw. Dahl would find success on his own with the books Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and James and the Giant Peach, both of which were made into successful films -- the latter by Disney.

With the success of Joe Dante's 1984 Gremlins film and its 1990 sequel, many believed the original Dahl/Disney concept was dead. Almost everyone felt that the public would forever associate the concept with that live action adventure. It took an adventurous publisher to show the experts that they were wrong.

In 2006, Dark Horse Publishing -- working closely with Disney -- reprinted Dahl's original book, complete with a new introduction by Leonard Maltin. The new edition was a success, capturing the attention of both those who remembered the original and those who were too young to know that Disney's Gremlins had ever existed. In addition, Dark Horse has introduced a new series of figurines to commemorate Disney's Gremlins and baesd a new comics mini-series around the sprites. The work of Dark Horse strives to be accurate to both Dahl's vision and the original Disney art that fans have grown to love.