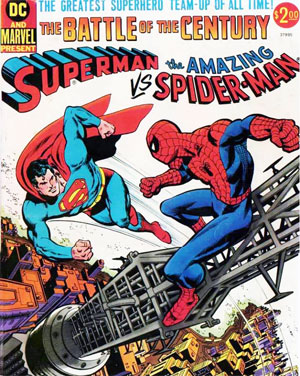

I dug in a little into the idea that even though they share prominent creators and have influenced each other back and forth over the course of the last 50 years, the DC and Marvel Universes have some fundamental differences in the way they’re structured. One of the things I really wanted to get across in that column was that neither one is really fundamentally better than the other, they’re just incompatible in a lot of ways, and I touched on how that results in something I call The Problem. Since that’s still pretty fresh in everybody’s mind, and since you were nice enough to set the ball right on the tee and hand me the bat, I might as well elaborate on that now. It’s actually pretty simple.

To put it bluntly, The Problem is that DC wants to be Marvel, and they have for the past 50 years.

Marvel and DC ComicsI call it The Problem and I think I have a pretty good reason for that, but to be honest, that desire has actually led to some of the best DC stories ever printed — arguably some of the best comics ever printed, so it’s not entirely a bad thing. The thing is, when you look at the history of those two companies and how they’ve fed off each other, you start to see what looks like an inferiority complex that’s driven decisions about the direction of their stories that seems to be there for decades, across multiple creators and editors, and once you notice it, the evidence just keeps on mounting up.

To really understand it, you have to understand what a profound change the arrival of Marvel comics was to the superhero genre, and to do that, you really have to go back to the beginning. DC — or at least, the company that would become DC — is there from the very beginning of superheroes as we know them. For all the scholarly talk about how sequential art goes back to cave paintings and how the early superheroes were just the next step from pulp novels (which is true), the superhero comic as we know it was born with Superman and Action Comics #1. DC is there on day one, and everything that comes after, right up to today, is directly descended from that one comic. And there’s a lot that comes after, too, and it starts right away. Superman’s popularity launches this massive boom in the Golden Age that sees a thousand imitators springing up overnight, creating this huge amount of material, most of which most comics readers have never even heard of, and probably wouldn’t care about if they had, and with good reason. I recently wrote about how modern Siegel and Shuster’s Action #1 story feels, but for every Golden Age story from Jack Cole or Will Eisner that feels like it’s years ahead of its time, there are a dozen that are almost unreadable for how flat they feel — and that’s coming from someone who actually likes a lot of those weird old books.

Now, within a couple of years, Marvel — or at least, the company that would become Marvel — is there too, but not really. Not in the form we’d recognize, even though Stan Lee, Jack Kirby and a couple of characters like Captain America are already in place. They’re laying groundwork for stuff that’s going to come after, but at the time, they’re not really anything DC needs to worry about, and before too long, there won’t really be anything for DC to worry about.

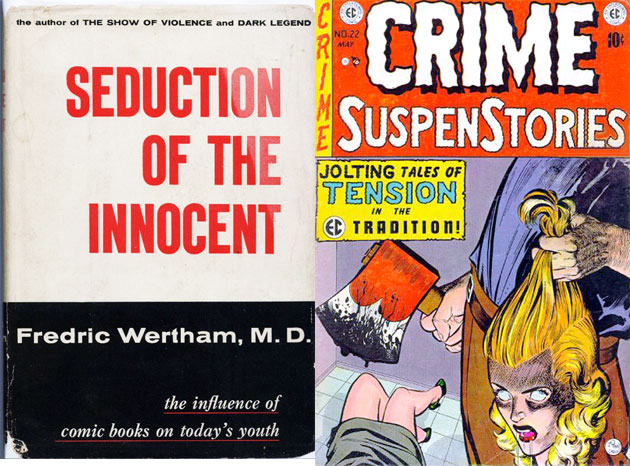

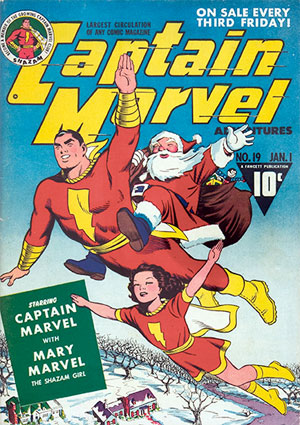

Five or six years after Action Comics #1, the Golden Age boom is in full swing, but ten years after that, there’s nothing that even comes close to challenging DC for dominance in the world of superhero comics. Superman in particular had become an instant American icon, and even though Batman started off as a pretty blatant ripoff of the Shadow, it wasn’t long before creators like Bill Finger, Sheldon Moldoff and Dick Sprang had forged him into his own character. They had that unmistakable aura of being the originals, and that went a long way towards cementing them in pop culture, fueling DC to some pretty incredible heights. That company steamrolled its way through the ’40s and ’50s, knocking out its competition with a ruthless efficiency until it was pretty much the last man standing. This is oversimplifying it a little, but what they couldn’t outsell or outlast, they either bought or just flat out destroyed. When Fawcett’s Captain Marvel was outselling Superman, they sued to put the kibosh on that, claiming he was infringing on Superman, and when EC’s horror comics were toppling superheroes out of dominance, DC (along with MLJ, the company that would become Archie) were the ones pushing for the Comics Code that would effectively neuter EC and put their biggest competition into an early grave in the name of Protecting America’s Youth.

More importantly than that, though, they didn’t just eliminate their competition: they absorbed them. When Quality went down for the count in 1956, for example, DC picked up Plastic Man, Blackhawk and a few other characters and dropped them right into their burgeoning universe. This wasn’t limited to the Golden Age, either. They’d eventually get the EC books (and MAD Magazine) too, and the Charlton books (Blue Beetle, Captain Atom, and all those) in the ’80s. While it would take them a while to finally acquire Captain Marvel, they got something more important out of it than the character. They got Otto Binder, the writer of those classic Captain Marvel Adventures stories, who would go on to be the definitive Superman writer of the ’50s, and certainly one of the most influential of all time. His tenure at DC saw the creation of some of the most popular elements of Superman, the stuff that’s still in use today. Supergirl, Kandor, Bizarro, the Legion, the concept of the out-of-continuity “imaginary story,” — those are Binder stories. He didn’t create Jimmy Olsen (Jimmy, the Harley Quinn of his day, was an import from the radio show), but he certainly defined his character and with it, the feel of the Silver Age. And he did it by just continuing the style he and CC Beck had been honing on CMA.

The irony of DC suing Captain Marvel because he was too similar to Superman, and then hiring a writer to make Superman more like Captain Marvel is staggering. It’s almost on the level of Archie destroying EC’s popular, lurid horror comics and then doing a zombie comic with incestuous Cheryl Blossom subtext, but at least they waited 60 years for that one.

The point I’m making here is that from the very beginning, this is how DC as a company has dealt with their competition. What they can’t destroy, they absorb. They’re like Dracula (DraCula?), and like Dracula, it often leads to some pretty awesome stuff. I wouldn’t trade those Binder Superman stories for all the Captain Marvel comics in the world, just like I wouldn’t trade some of the other stories that this brought.

While all this was going on, DC was thriving. Huge sales in comics, sure, but also as a pop culture phenomenon. It cannot be understated how much of a cultural impact Superman in particular had — the Superman radio show was the medium used to bring down the Ku Klux Klan by exposing their secrets, for Pete’s sake. That’s a big deal.

And while all that was going on, Marvel (or Atlas, or Timely, you know the drill by this point) was just sort of there, hanging out, trying to get things going. Mostly they stuck with romance comics (a genre Jack Kirby and Joe Simon invented) and monster books that were more or less watered-down versions of the EC formula with proto-kaiju and predictable twist endings, and while I wasn’t there, I almost have to imagine that part of that was because there wasn’t much of a percentage in mixing with DC in terms of superheroes. DC had its own horror comics and romance titles, but then, as now, they weren’t really the key part of the line (though, you know, they at least had them). DC was focused on superheroes, and since they had the most popular superhero ever created, and the second most popular superhero ever created, and the third, and the fourth and the fifth, and Aquaman, what’s the point of even trying to compete with them? How do you even begin to take on Superman?

Well, if you’re Stan Lee and Jack Kirby and you’ve been watching all this go down for the past 20 years, it’s easy. You just sit down one day and reinvent the superhero comic. No big deal.

Which is exactly what they did. I’ve talked about this before, how the Marvel comics are deceptively simple in how they work. They’re undeniably adventure comics, the same kind of superhero stories that DC’s publishing, only they add in the stuff they’d been working on for the past decade. The twists and horrified reactions of the monster comics, the angsty, unrequited yearning of the romance books, and just bundle it all together in a book that doesn’t look like anything else on the stands. That last part is easy, because at this point, the only thing worth mentioning on the stands is DC, and they all have a pretty similar look. Wayne Boring, Al Plastino, Curt Swan and Kurt Schaffenberger are all phenomenal artists (Schaffenberger is probably the most underrated and overlooked Superman artist of all time, and his work is flat-out gorgeous), but to a certain extent, their art all sort of looks the same. There are differences and styles and you can tell them apart, sure, but they’re definitely part of the same school.

Jack Kirby is not.

So in 1961, Kirby and Lee take a gamble and put out Fantastic Four #1, a new kind of superhero comic…

…and people Lose. Their. S**t.

Marvel and DC’s November 1961 offerings. Superman’s toughest day doesn’t seem all that tough by comparison.

It might not have been an overnight success — there’s that legendary story of Martin Goodman giving up on Marvel and shutting down the offices and Kirby arriving and throwing out ideas like “Let’s bring back the Sub-Mariner! Let’s bring back Captain America!” in a last-ditch effort to strike gold while the workmen are trying to take the furniture out of the buildilng — but it doesn’t take long before Marvel develops a pretty huge fan following. And the way they do it, the way they cultivate it, isn’t just through the books themselves.

Obviously, the books are a big part of it and didn’t really need any help standing out against DC’s Silver Age fare. By all accounts, Mike Sekowsky was a treasure of a man and a consummate professional who could hit a deadline like a prize fighter, but his barrel-chested Justice League looks like a bunch of cardboard cutouts next to Steve Ditko’s weird spindly limbs and twisted grimaces or John Romita’s solid, romance novel cover models running around in Spider-Man. Whether they like it or not, everyone knows Marvel’s doing something different. But that’s only half of how they set themselves apart.

The other half, quite frankly, might be what made all the difference, and you can lay it at the feet of exactly one man: Stan Lee.

You can argue for hours, days even, about Lee’s proper place in history, about whether he deserves the starry eyed admiration of the general public who think he’s the sole creator of everything there was in the Marvel Universe and whose shoulders bore the monumental, nearly unthinkable task of scripting every single classic of the early days of Marvel, or whether he deserves the scorn of the Kirby and Ditko partisans who see him as a funky flash-man who attached himself like a parasite to more talented artists and then used them to catapult himself (and only himself) into the spotlight every chance he got. I think the truth of that is somewhere in the middle, but there’s one thing you can say about Lee that I don’t think anyone’s going to dispute: He’s the ultimate salesman. Lee is, to this day, a self-promoter of unfathomable skill, and in those early days of Marvel, he was in his prime.

He was not there to make friends. He was, in fact, there to make enemies.

Lee realized, just like everyone else, that Marvel was doing something different from the competition, so he used the soapbox of letter columns to set up the idea that it was time to take sides, laying out that Marvel and DC were engaged in open conflict for the readers, and the Marvel books were constantly telling you that you were smart for reading Marvel books instead of Brand Ecch. If you go back and read those “Fantastic 4 Fan Pages” from the early years, they’re like these bombastic diss tracks, and Stan’s writing “Ether” every single month. It’s actually kind of hilarious: At one point, it gets so bad that people who like Marvel and DC write in to ask Stan to please stop insulting them at the end of every issue. Stan, in true huckster fashion, puts this issue to the readers with a poll: Should they keep talking about how much DC sucks, or focus instead on how much Marvel rules?

Incidentally, DC’s letter columns at the time would occasionally feature Robert Kanigher just straight up being a dick to people who wrote in nitpicking stories, basically telling readers to get a life. They are also hilarious, but it’s not really difficult to see why Stan didn’t have much of a hard time getting this adversarial relationship going.

The key point of Stan’s argument is that Marvel’s offering a more “sophisticated” choice, and to be fair, that’s fairly accurate — but only in the way that DC’s making comics for kids, and Marvel’s trying to corner the teen market. This, it’s worth noting, was the dawn of the teenager as an economic powerhouse, and that made a huge difference to the evolution of comics as much as it did to everything else. You can see that reflected across all of pop culture as everyone tries to capitalize on it, whether it’s Marvel comics and their soap operatic angst or, you know, the best song ever written. It all happens at once, and it was inevitable that it was going to happen in comics — Marvel just got there first, because DC had no real reason to change just yet.

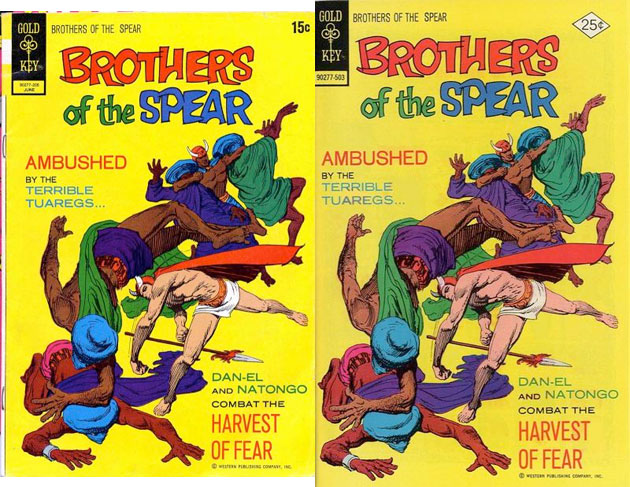

So Marvel becomes a success. Even more than that, Marvel becomes a success with the exact crowd that DC was losing anyway as they aged out. This was a fact of the industry for a long time, too — Gold Key, one of the other comics publishers at the time (though not one that ever really made any headway in superheroes) used to actually have a policy of just reprinting the same ten or twelve stories over and over again, because they figured they only had a two-year window of readership. Kids would get into M.A.R.S. Patrol or Brothers of the Spear when they were twelve, and by the time they were fourteen, their interest would inevitably turn to, I don’t know, baseball. Since you only had them for two years, why bother making more than two years worth of stories? Just cycle through them, because by the time you hit the next round of reprints, everyone who read them last time has discovered making out and is no longer interested.

Brothers of the Spear #1 and #12. Significantly less interesting than making out.

Brothers of the Spear #1 and #12. Significantly less interesting than making out.

It strikes me as a pretty defeatist attitude, and is probably the reason I’m not writing about the key differences between DC, Marvel and Gold Key, but, you know, whatever works for you.

Marvel changed all that by the simple act of catering to a slightly older audience. Instead of the average comics reader getting to the point where they were no longer being served by DC and therefore no longer being served by comics, period, there was now something that was designed to stretch that interest for a few more years. As a bonus — another trick picked up from soap operas — Marvel’s stories weren’t the concise, self-contained eight-pagers that ran in DC books. They were one continuing epic where each installment was fully built on the last, where nothing ever ended back at the status quo. There was always a cliffhanger to keep the reader coming back, even when it seems weird not to finish something. A while back I wrote about Fantastic Four #50, and how the most surprising thing about it was that after raging for two issues, the Galactus story ends halfway through the book, and then it’s off to visit Johnny at college to start up the next thing.

Again, even while Marvel became a success, DC was not exactly hurting at the time. Far from it, in fact — while the FF were fighting Galactus, Batman was in prime time in a show that was wildly popular. There’s a weird desire in certain parts of comics fandom to minimize the Batman show, but it was a massive hit, to the point where “Batman, the Beatles and Bond” were considered to be the “three Bs of the ’60s.” That’s pretty great company to be in, folks. It was also, despite another annoyingly persistent myth, actually pretty faithful to the comics of the time — this January, DC’s actually acknowledging that after 48 years by putting out a collection of the stories that were used as episodes. I could not be more excited about that.

Point being, DC’s formula was still more or less working for them. Obviously styles were evolving, but that’s going on all the time. The thing is, after a few years, it becomes pretty apparent to everyone that Marvel’s not going anywhere, and DC finally has an opponent it can’t outlast and is starting to have a hell of a lot of trouble outselling. So they go with the tactic that they, as a company, always go to when they can’t afford to ignore something.

They try to absorb it.

The degree to which they succeed really depends on where you set the goalposts, but I’d argue that they didn’t quite get what they wanted. The universes are too fundamentally different to really do the job the way they want to do it. It’s easy to graft Captain Marvel onto Superman, but by the time DC decides they need to do something about Marvel, those radically different styles are already crystalized in ways that don’t fit together that smoothly. But they keep trying, for the next 42 years.

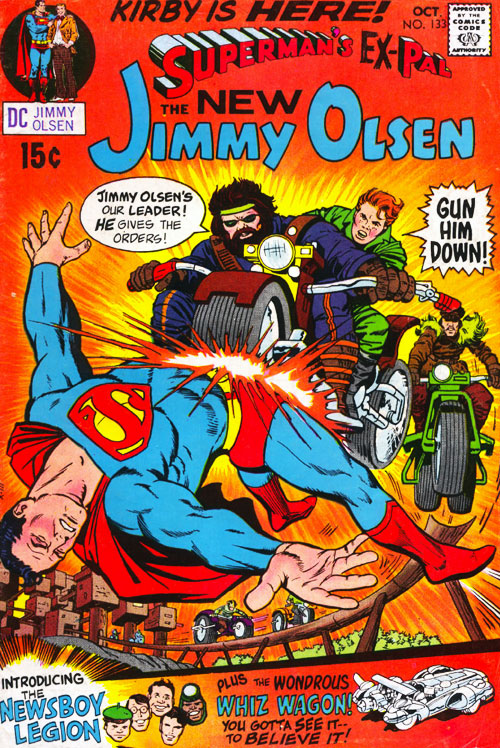

And like I said, it’s not all bad by any means. It’s actually something of a renaissance for DC, and it starts in ’71 with the most logical move DC could possibly make if they wanted to capture Marvel’s success: They hire Jack Kirby, which, with all due respect, is basically hiring Marvel. But see, this is the other part of The Problem: They know they want to be more like Marvel, but they don’t really understand how to get there, so instead of unleashing Kirby on the DC Universe (which, to be honest, probably would’ve been more jarring than anything else), they put him in this weird little box. For the most part, they let Kirby do what Kirby does, which is create new concepts, and from that we get a ton of amazing stuff added into the DC Universe: Darkseid and the New Gods, Etrigan the Demon, OMAC, Kamandi, far futures and distant pasts, cosmic and magical, and it’s all great. But they don’t do the one thing you’d expect them to do. They don’t put him on Action Comics and have him usher in a bold new era of weird cosmic Superman stories in the flagship book. They put him on Jimmy Olsen.

Again, I love Kirby’s Jimmy Olsen, but it’s such a weird book to put him on, and it shows how little faith they had in Kirby while at the same time wanting him to give their universe a touch of that Marvel magic. It’s a little early for a lot of people, but I’m of the mind that you can mark the end of the Silver Age and the start of the Bronze Age from the exact day that Jimmy Olsen #133 hits the stands. Jimmy was such a product of the Silver Age that he couldn’t have existed as he did at any other time in comics history, but the second Kirby’s on that book, there’s no going back. The Silver Age is over. Which, of course, is exactly what DC wanted, to have their books feel more modern and to appeal to the teens, to blunt the backlash of fans who thought Batman ’66 had been making fun of them.

And yet, they send in Silver Age mainstay Al Plastino to re-draw Superman’s face so that things don’t get out of hand.

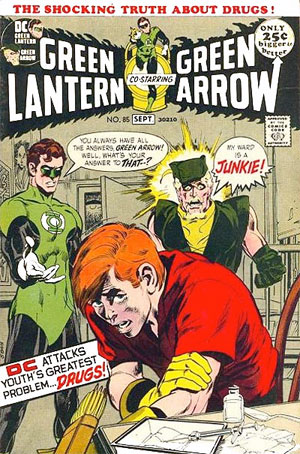

Green Lanern #85What follows is a decade of DC trying to play catch-up. Peter Parker deals with campus riots over housing for low-income students, goes through hard economic times and watches Harry Osborn take acid in Amazing Spider-Man, so DC sends a space cop with a magic wishing ring and a Robin Hood cosplayer on a trip across the country because one of them didn’t know racism existed and the other didn’t know drugs existed, and the result is one of DC’s most highly regarded stories. The same team that did that one, Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams (who had worked together before at, surprise, Marvel) would also produce some amazing Batman stories, but O’Neil would be given the assignment to reduce Superman’s power, bringing him more in line with these flawed Marvel heroes. He teamed up with Curt Swan to do it, but in another sign of DC being skittish and not quite knowing what they want, the changes are reversed in record time. Late in the decade, they lure Amazing Spider-Man writer Gerry Conway over from Marvel, and he and Al Milgrom (another Marvel mainstay) create Firestorm, who is exactly what you’d expect from a DC attempt to do a Spider-Man story in the ’70s. You can see it happening all over the era.

And then you hit the ’80s, and Operation Make DC More Like Marvel goes nuclear.

It starts with New Teen Titans, which is maybe the most blatant attempt at playing catch-up to Marvel by giving them a team book that would be comparable to the endlessly popular X-Men, created by two guys who had made their names across the street at — surprise! — Marvel Comics. Wolfman in particular hadn’t just written six years of Tomb of Dracula over there, he had a cup of coffee as editor-in-chief. That’s how much of a Marvel guy Wolfman was at the time, and Perez had worked with Roy Thomas and Jim Shooter on Fantastic Four and Avengers. As a sidenote, in the same way that I mark the end of the Silver Age by Kirby’s arrival on Jimmy Olsen, I have a friend who mars the end of the Bronze Age by Perez’s arrival at DC, stepping in to draw Justice League when long-time DC artist Dick Dillin died in the middle of an arc. It’s a huge departure in style that’s almost as jarring, and when you consider what comes after, it makes a lot of sense.

New Teen Titans was a smashing success in building a book with the mix of action, adventure, romance and drama that Marvel had revolutionized superhero comics with, but for the purposes of this story, it pales in comparison to what comes next. When DC sees the success they can have by actually committing to becoming more like Marvel, they decide to go all in on a scale that no other publisher has really done since (although they’ve done it a couple more times themselves, to varying degrees of diminishing returns): they scrap the entire universe altogether in Crisis On Infinite Earths and build one that’s more like Marvel.

One interesting note about Crisis that underscores it all is that one of Wolfman’s ideas for the new DC Universe that would result was actually going as far as renaming the company from “DC” (short for “Detective Comics,” the piece of trivia everyone knows) to Action Comics, but it was shot down because “DC” had the name recognition. Personally, I think Wolfman was absolutely right. It has the same connection to the history of the company and actually makes more sense given that it’s the book that launched everything, and perhaps more importantly, “Action” is exactly the kind of intriguing, enticing brand name for something that “DC” isn’t, and that “Marvel” is.

This is the key point, and it’s the one that’s glossed over to an almost maddening degree. The reason they always state in the company line is that the Pre-Crisis was just too darn complicated for “new and occasional readers” — that’s how they phrase it in the recent Superman 75th Anniversary hardcover — and it makes a certain kind of sense when you consider that stuff like knowing the difference between Earth-2, Earth-X and Earth-C was considered the arcane realm of annoyingly detail-oriented True Fans™. Really, though? It’s one of the biggest and most persistent lies in the history of DC Comics, albeit one that ranks significantly lower than “Batman Created By Bob Kane.”

It’s complete bulls**t, and we know that for a variety of reasons. First, the DC Multiverse wasn’t actually used that often. It showed up once a year in Justice League for their annual crossover, but beyond that, it wasn’t really used any more than any other plot device, unless you were, you know, Rascally Roy Thomas (another Marvel import who’d been EiC at the House of Ideas), who really, really loves the Golden Age characters. Second, and probably most damning for the “it’s too confusing” line, I can assure you that if you actually read a comic about Earth-2, they were not going to let you forget it. They would go out of their way to let you know what you were dealing with and the idea of parallel worlds was explained WITH DIAGRAMS virtually every time it showed up. You were about as in danger of being confused by Earth-2 as you were by Superman putting on glasses and this Clark Kent guy showing up out of nowhere. Third, if the multiverse was so deucedly complicated, they prrrroooobbbbably wouldn’t have almost the exact same multiverse in place now.

And yet, that lie persists, and ironically, it’s often brought up by Marvel partisans to explain why Marvel was so much better than DC, as though “there’s another Earth with another Superman, only he’s older” is in any way even remotely as complex as, say, any two-year stretch of X-Men comics between 1989 and the present.

Looking back, there’s only one logical reason to want to throw it out: Because Marvel didn’t have a multiverse. Well, except that they did, but they kept it confined to one book hosted by some creepy bald voyeur that nobody actually liked, other than that one about Conan being stranded in the present and walking around with a pet leopard, but we’re getting sidetracked. The sole reason for it is that they wanted to be more like Marvel — they even did it as a twelve-part world-shaking event because that’s what Marvel had done a year earlier with Secret Wars — and all the evidence you need to know that’s true is in how they rebuilt.

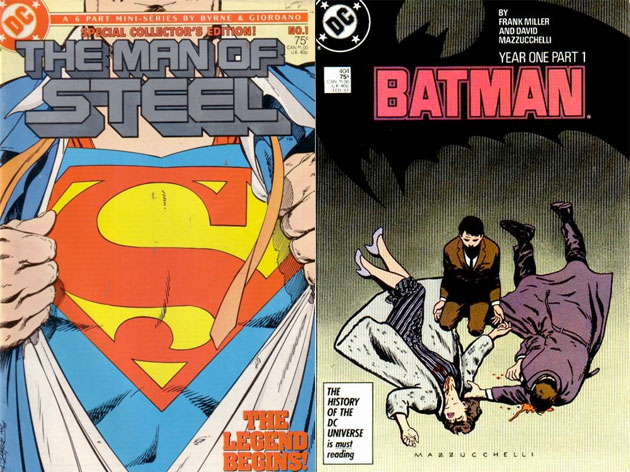

When it came time to redefine their major characters, here’s who DC got: John Byrne on Superman and Frank Miller on Batman. Perez would come in a few years later to rebuild Wonder Woman, but in 86, those were the guys, and they could not have been more Marvel Comics. It should be noted that Byrne in particular had wanted to do Superman forever. There was a time during the Shooter era when Marvel actually came really close to just buying, or at least getting the publishing rights to the DC characters from Warner Bros., and when Byrne heard about it, he had his pitch ready within about nineteen seconds. It fell through, obviously, but Byrne got the job after Crisis, largely because of the massive success he’d had on X-Men (of course) and Fantastic Four, the most Marvel title of ‘em all.

Miller’s a much more interesting case in a lot of ways. What always gets glossed over about Miller and Batman is how little there actually is, and when you get right down to it, there are really only eight issues. Okay, no, there’s actually about 20ish if you count penciling “Santa Claus: Wanted Dead Or Alive” (which I do) or the recent stuff like Dark Knight Strikes Again and All Star Batman (which I don’t), but really, those endlessly influential building blocks of modern Batman? Eight issues. Two stories. Two incredibly influential, monumentally great stories, but two stories. I’m not sure if I buy it, but you can make a case that just by sheer volume, the Frank Miller comic that influenced Batman most wasn’t a Batman comic at all. It was Daredevil. That’s certainly the book that got him and David Mazzucchelli the job redefining a vigilante for a crime-ridden urban sprawl.

The weird thing about these two stories in particular is that they get these guys that are so strongly identified with Marvel titles and, with Miller, they get a story that feels undeniably like a DC title, albeit one with the same grim elements that you find in Daredevil. Everyone remembers the grittier parts of Year One with the crooked cops, Catwoman as a dominatrix and the hard-boiled narrative, but at the end of the day (and the end of the fourth issue), that’s a book that’s steeped in optimism, where One Man Can Make A Difference and where Batman jumps off a bridge and catches a baby and survives. In Marvel comics, people tend to have a much harder time with being thrown off of bridges.

Byrne probably comes the closest to doing a Superman that fits that Marvel aesthetic, if only by virtue of drastically reducing Superman’s (ugh) canonical power level and then capping off his run with a story where Superman executes three pocket universe Kryptonians and then leaving the other writers of the book to deal with all the baggage that brings along, but he did a lot to preserve what was there at the core of Superman. Man of Steel (the comic, not the movie) is still my standard for Superman origins for exactly that reason, although it’s worth noting that his major, lasting contribution to the universe was recasting Lex Luthor as a sinister industrialist rather than a professional mad scientist supervillain — which is a very Marvel Comics way of doing things.

Incidentally, did you catch “pocket universe” in that last paragraph? Two years, folks. That’s how long the death of the DC Multiverse, the entire stated reason for Crisis, managed to last.

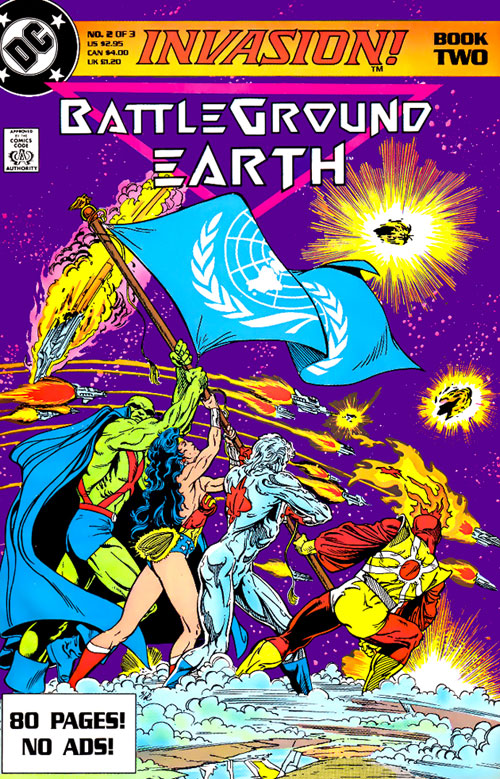

If that wasn’t enough of a sign that DC was trying to hammer itself into something more similar to the Marvel Universe, there are other signs all over the place. The Justice League, for instance, was recast without the big-name heroes into a team book built on contrasting personalities that felt more like the ’80s Avengers, and when you hit the ’90s and Marvel rolls out with stuff like X-Force, you get DC hopping on the bandwagon with Extreme Justice, but the exclamation point on the whole era was probably INVASION!, a comic that actually had an exclamation point in the title. It’s my favorite event ever, partially because it’s so quick (three 80-page giants illustrated by Todd McFarlane before he jumped ship and started drawing Spider-Man) and partially because there are so many good tie-ins, but when you get right down to it, INVASION! is almost hilarious in how much it’s attempting to be Marvel. For one thing, it’s the only DC story written by Bill Mantlo, one of the key writers of Marvel’s Bronze Age (and one of the most tragic stories in comics, please help if you can), but then there’s the consequences. The big result of the whole thing? Invading aliens drop a “gene bomb” on the population, triggering latent “meta-genes” in the population and activating super-powers in a small percentage.

In other words, it brought mutants to the DC Universe.

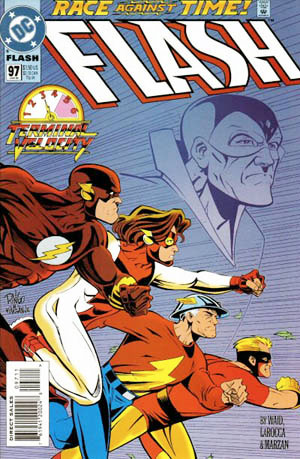

It’s worth noting that this led to another creative renaissance for DC, and that despite the desire to compete with Marvel on their own terms, the ’90s DCU was defined in a way that was uniquely its own. This is something else I’ve written about before, and it’s the reason Mark Waid and Mike Wieringo’s Flash is arguably the most important DC Comic of the ’90s, because it’s the comic that was firmly rooted in the idea that would distinguish DC from its competition: The idea of Legacy.

When they collapsed their alternate universes into one, they did the one thing those multiple Earths were explicitly designed to prevent: they put everything on a timeline that dated back to the actual creation of those comics. It took a little massaging over the years, but eventually that came to work in its favor, by establishing that the DC Universe was built on this tradition of heroism that stretched back to 1939, with superheroes from World War II, where the heroes of past eras could pass their titles down to a current generation. There are obvious problems with this, of course, because it forces you to choose between having a Superman who’s current and “young” and a Superman in his rightful place as the first superhero, but you know, there were ways around it. Heck, they’d already created characters like Etrigan who dated back thousands of years, so the “Superman is the first” ship had already sailed. The idea they settled on was that there were heroes for a while, and then there weren’t, and then Superman comes along and ushers us into a new age of heroes that’s bigger and better than anything before.

It’s a great idea, and it’s what led to books like Flash, where it was a primary theme, and in Green Lantern, a book that had die-hard fans who apparently weren’t aware that having 3600 versions of a character means that he can be replaced, and even in the Batman titles, where Robin was the role that progressed as time went on. It was a good idea that led to great stories, and best of all, if you’re trying to distinguish yourself from your rival, it was something Marvel didn’t have.

Marvel, for better or worse, has always been about what’s going on now, and a lot less eager to look back at its own past. That’s the spirit of Kirby running through those books, I think, but the result is that if it’s always now, it was never really then. Peter Parker never was Spider-Man, he is Spider-Man, and while there are often attempts to shake things up by putting a new character into a role, it never really lasts. While DC was building the idea of a progression — from Jay to Barry to Wally, from Alan to Hal to John to Guy To Kyle, from Dick to Jason to Tim, etc. — Marvel’s standard method was to bring someone in for a while and then have them graduate to the new character to their own role when the original version came back. Rhodey fills in as Iron Man, then becomes War Machine. Eric Masterson fills in as Thor and then becomes Thunderstrike. Ben Reilly fills in as Spider-Man and then the angry shrieking gets so loud that we just stuff him in a metaphorical woodchipper until enough time passes that we miss him. It’s the circle of life. And it’s also the policy that DC adopted when they hit the reset button again in 2011, restoring the likes of Barry Allen and Hal Jordan to their previous roles.

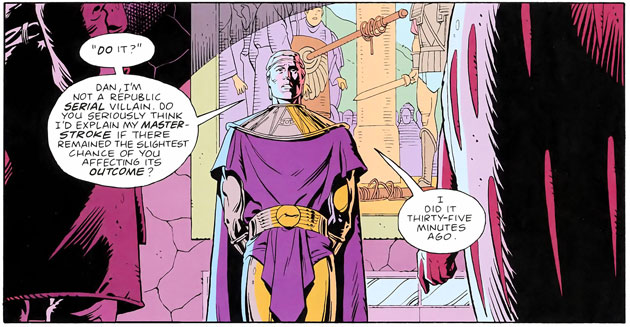

For a while, that was the way things were, and weirdly enough, this is also the part of history where Marvel straight up goes bankrupt, and DC, for the very first time since 1961, is perfectly cool with not being Marvel anymore. But it didn’t last, largely because of The Other Problem, which is — and I swear I’ll keep this one short — that DC got it into their collective head that they needed to be Very Serious. This is an extension of The Problem that goes back to the days when DC Comics were for kids and Marvel Comics were for teens, and DC raged like a little brother because it didn’t want to be for kids, it wanted to be for grown-ups. At the same time that they’re restructuring their universe to be more like Marvel, they’re also publishing the comics that will get them the most critical success that they will ever have, the ones that I don’t even really need to identify by name because you all know where this is going, but I will anyway: Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen, Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns and, just as importantly, Moore and Steven Bisette’s Swamp Thing, among others.

And once again, people Lose. Their. S**t.

Biff! Pow! Comics aren’t just for kids! They’re not even comics anymore, they’re Graphic Novels so put it in the suck it bucket, Adam West! And the thing is, they’re not just mature readers comics, they’re actually really good, and so are a lot of the others that spring up around this time, whether they’re coming from the Indie Boom of the ’80s or winning Pulitzer Prizes like Maus. And DC, the collective entity that is DC as a company, the one I’ve been personifying for the entire column, sees this and has a revelation.

“Aha!” says this imaginary version of DC, “I get it now! The reason they liked Marvel, which was going for a slightly older audience, the reason I had competition that cut into my sales after bestriding the Earth like a mighty colossus for three solid decades, was that they wanted things that were mature. All that stuff that I used to do that was for kids, about cartoon characters with superpowers facing down weird situations, that wasn’t mature. They want violence and blood and cusswords and crying and moping and boy howdy they definitely want a whole lot of rapes. And since I can only do one kind of thing, that is what I must do.” Seriously, they have been chasing that dragon so hard that they actually did more Watchmen comics in an effort to drum up past glory. It creates this weird corporate schizophrenia where they want to look back at the high points of their past, but want them to be more Very Serious than they actually were. This is The Other Problem, and it’s why we have Identity Crisis and a Superman movie with no bright colors that ends with death.

And then DC slowly begins the process of trying to make that vision a reality. In the mid 2000s, Marvel has come back from bankruptcy and it gets so bad that DC does two comics — Identity Crisis and Justice League: Cry For Justice — that are so hellaciously ruinous that they pretty much have no choice but to throw the baby out with that foul tub of bathwater and start over again. And this time, they hire yet another former Marvel Editor-In-Chief, Bob Harras, to run the show. And that pretty much brings you up to today.

And again, it’s worth saying that there’s good, even great work coming out of DC this time around, too, even if the overall mood of the universe, if such a thing even exists, feels like a relentless grind to get through sometimes. But that, in turn, raises the question of why, if there are so many amazing comics that result from this, from The New Gods in ’71 to Hard Traveling Heroes to Batman: Year One to Flash to Zero Year, is this The Problem? If there’s that much good that results from it, then shouldn’t it be, at worst, The Curious Affectation?

The reason that it’s The Problem is because of how it makes them look at their characters with this eternal inferiority complex that can never really be resolved. That fundamental difference between the universes that I mentioned above and wrote about at length last week means that if they want to be Marvel, they’re never actually going to get there. They’re just going to keep tying new ways to get there and resetting when they realize that they’ve only complicated matters, and it’s all so unnecessary. Superman doesn’t need to be anything else, he’s already Superman, and the same goes for Batman, Wonder Woman, and the rest of those characters. They can be better, sure, but the way you make them better is by sitting down and asking “how can this be better,” not by asking “how can this be more like that other thing?” You get good stuff out of that, yes, but you also get Superman executing criminals and Extreme Justice, and that’s the kind of thing we can do without.

For their part, Marvel pretty much seems like they could give a f**k.