It’s rare when something that’s 70-years old can do anything as well as it did when it first came on the scene. For instance, a 70-year old man probably can’t get it up like he used to, houses and buildings that have seen that many decades have also seen their share of rust, rot, and cracks, and the most likely place you’ll find a car from the 1930’s that still works is in Jay Leno’s garage (assuming it isn’t stolen. Too soon?) And yet, those who love movies, I mean those who really love cinema can attest that 70-year old movies are just as powerful and effective as anything released today. Don’t believe me? Then do yourself a favor and pick up Tod Browning’s Freaks. Directed by the man best known for first bringing Dracula to the screen in 1931, Freaks was made just one year later and due to its disturbing and uncomfortable content, it basically destroyed his career ala Michael Powell with Peeping Tom.

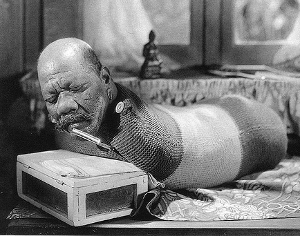

Now, I know what you’re thinking: “disturbing subject matter” in 1932 probably translated to something that would be considered tame nowadays such as a woman who shows too much of her bra strap (harlot!) or a man who says “hell” too much (blasphemer!). If that be the case, you would be mistaken. The disturbing subject matter in Freaks is of the holy-shit-how-did-he-ever-get-away-with-this-it-will-be-haunting-my-nightmares-for-days variety. You see, Freaks, as the title implies, features real-life circus sideshow performers as the main characters. These aren’t your run-of-the-mill county fair sideshow performers like unusually hairy or overweight people either; the cast includes midgets, a man with no legs who walks on his hands, another who has no limbs at all, and multiple microcephalics, or “Pinheads” as they are so dubbed. The disturbing subject matter comes from the plot in which all these “freaks,” these shunned and segregated members of society are all brought together for one haunting yet profound tale of greed, intolerance, and revenge.

The story revolves around Hans who, despite making his living as a midget in a circus, has inherited a fortune. He swoons over Cleopatra, the “big person” trapeze artist who has no qualms with laughing at the physical and verbal abuse the “freaks” suffer at the hands of other circus members. When she discovers Hans has a fortune waiting for him, she plots with her love Hercules, the circus strongman, to ruin Hans’s marriage to his midget wife, Frieda, then posion him and inherit his money. For a while, everything goes according to plan with Hans falling for the bait hook, line, and sinker, upsetting the rapport and harmony that exists within the small circle of the circus’s sideshow performers. While Frieda mourns the loss of her husband, one of the performers chides “[Cleopatra's] not one of us.”

The story revolves around Hans who, despite making his living as a midget in a circus, has inherited a fortune. He swoons over Cleopatra, the “big person” trapeze artist who has no qualms with laughing at the physical and verbal abuse the “freaks” suffer at the hands of other circus members. When she discovers Hans has a fortune waiting for him, she plots with her love Hercules, the circus strongman, to ruin Hans’s marriage to his midget wife, Frieda, then posion him and inherit his money. For a while, everything goes according to plan with Hans falling for the bait hook, line, and sinker, upsetting the rapport and harmony that exists within the small circle of the circus’s sideshow performers. While Frieda mourns the loss of her husband, one of the performers chides “[Cleopatra's] not one of us.”

During the wedding feast, the performers, Hercules, and Cleopatra all get together to celebrate the new marriage and as they pass around the Wedding Cup - a communal cup of wine - they chant “gooble gobble, gooble gobble, we accept you, we accept you, one of us, one of us” to declare to Cleopatra that she is now welcome as a part of their family. Completely shit-faced, Cleopatra can no longer hide her disgust at the physical abnormalities around her and unleashes a tirade against them, shouting, “Freaks! Freaks! Freaks!” Having seen her true colors and eventually uncovering her plot, the performers come together to plan revenge. On a dark and stormy night, after one of the wagons in the circus caravan tips over, they exact that revenge. As the lightning flashes and the rain falls, the performers crawl through the mud after Hercules and run through the pitch black forest after Cleopatra, the blades they carry shining with each bolt in the sky. It’s the most bone-chilling rainy night ever caught on celluloid and watching it still sends shivers down my spine.

Though the brutality is never shown on screen, the result certainly is. With a simple crossfade, we later see Cleopatra in a sideshow of her own - legs severed, face irreparably scarred, wearing a chicken suit and clucking at horrified onlookers. She has become that which she found disgusting. If you watch the sequence of events and don’t find your blood running cold or the images burned into your brain when you close your eyes at night, then check your pulse - you might be dead.

Despite how the above events may sound, Freaks is surprisingly sympathetic in dealing with the sideshow performers. Browning, a former circus contortionist himself, essentially came from the world he depicts on film, and it’s clear from the start that despite their disabilities, Browning values them as people no less than he does the “big people.” Indeed, the film begins with a speech by a man who declares to the crowd that “but for the accident of birth, you might be even as they are” and there are multiple scenes throughout the film that document them as playful children, proud parents, enamored lovers, and devoted friends. In short, they display the personalities and character traits that we value in all people of all shapes, sizes, and colors.

Browning does a fantastic job to accent the emotion ahead of the spectacle, and some of the scenes between a broken-hearted Frieda and the oblivious Hans generate true remorse and empathy because we relate to plight - not because we pity her, but because we can relate to her. Though they are scorned and mocked, they are told never to be afraid for ‘God looks after all his children.’

There are arguments, and not totally baseless ones, that claim the film is still exploitative, citing lingering shots that accent the performers’ deformities and adapted abilities and that claim their cold-blooded revenge casts them as a merciless gang of brutes who adhere only to some barbaric ‘code of the freaks.’ I can’t help but see this opinion as tainted by context. If the roles were reversed and the “big people” were the minorities who were mocked and scorned, would their extracted revenge be criticized for adhering to some barbaric ‘code of the big people?’

However, the initial argument is not completely without base either, and I think that’s because Browning uses the film to make us aware of our duality as “normal people,” in which we support a moral code of equality that we don’t necessarily practice. There are many times when it’s understandable to feel awkward and uncomfortable with what you see on screen. In particular, the wedding festivities feel foreign and almost cult-like with its chanting and host of irregular guests. It’s not completely off-base to feel like you’re viewing something abnormal. Yet when Cleopatra bursts out in rage and disgust, our moral pendulum swings in the other direction, and we’re immediately aware of our simultaneous anger at Cleopatra and shame with ourselves for internalizing what Cleopatra was so bold to express. So, is Browning actually exploiting them or do we only think he is because in the back of our minds we feel like they’re exploitable? 70 years later, it’s still worth discussing. If you can get past the nightmares.