May 8, 1940, Sterling North (eventually to write the children’s Newbery Honor Book Rascal) wrote in the Chicago Daily News that “color ‘comic’ magazines” were “a national disgrace” and that “parents and teachers throughout America must band together to break the ‘comic’ magazine.”

Mind you, it’s only fair to note that the art form was in its infancy in 1940. Not only was North not writing then about Bone or Owly—nor was he prescient enough even to consider the possibility of an evolution to Maus or American Splendor—he was writing before the advent of Will Eisner’s Spirit sections and, indeed, before Mickey Mouse Magazine had morphed into Walt Disney’s Comics & Stories.

He was throwing a figurative snowball at the industry at a time when the adventures of Superman had only been appearing for a couple of years and those of Batman (though inspired by earlier pulps featuring The Shadow) for only about a year. Much of what was appearing all in color for a dime in 1940 consisted of strip reprints. The “poisonous mushroom growth of the last two years” of which North wrote was clearly fed by costumed heroes rather than by the Walt Disney cartoons that had begun to provide characters for the expansion of the Dell line. But it’s fair to note that such an expansion was under way, with more to come in the following two years—admittedly along with a plethora of new villains to be punched out by many more costumed heroes. (One month after North’s essay, Eisner’s Spirit section first appeared in newspapers; the Golden Age Daredevil was introduced in Silver Streak Comics #6 before another year had gone by.)

On the other hand, by the time This Week ran “How Good a Parent Are You?” by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, World War II had come and gone, and comic books had widened their variety. Nevertheless, media attacks on comics had been renewed. Hoover’s April 20, 1947, article called “crime books, comics, and newspaper stories crammed with anti-social and criminal acts” … “extremely dangerous in the hands of the unstable child.”

But by then, readers were experiencing a Golden Age of great little kids’ comics as well as an ongoing source of tales of super-heroics—and more. Walt Kelly (whose Pogo was far from his only series), John Stanley (whose work on Little Lulu continued to go uncredited), and Carl Barks (who signed his Donald Duck tales as “Walt Disney”) were turning out generous monthly servings of gag-laden tales aimed at young readers. Moreover, such writers as Gaylord Du Bois were (albeit also usually anonymously) incorporating strong messages of social responsibility and equality in such series as Tarzan. But it may be wrong to assume that those attacking the field were actually reading the variety of comics, as opposed to looking for the most horrible possible examples to spice up their reports of alarm.

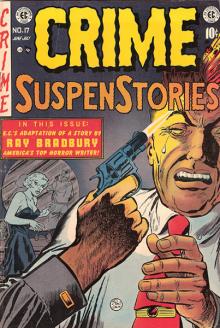

Crime SuspenStories #17 featured an adaptation of a classic by Ray Bradbury, clearly not aimed at children. But many critics sought to take such stories off sale, as the Senate heard less than a year later.

Crime SuspenStories #17 featured an adaptation of a classic by Ray Bradbury, clearly not aimed at children. But many critics sought to take such stories off sale, as the Senate heard less than a year later.

© William M. Gaines, Agent, Inc.

After all, even such a classic as Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy comic strip was the target of ongoing complaints. The term “crime comics” was especially employed by Fredric Wertham in his attacks on drawn stories. Tales of criminal activities had been a mainstay of pop culture for many decades before the term “pop culture” was invented. MGM, for example, had begun a series of 50 live-action shorts tied together with the “crime does not pay” theme in 1935 (now available on DVD). With the July 1942 issue, Lev Gleason had even changed the title of its Silver Streak to Crime Does Not Pay (also a tagline of the radio Shadow). Eventually, horror comics were added to comic-book targets, when Avon’s Eerie #1 (January 47) appeared: a one-shot credited with founding the field of horror comic books just a few months before the Hoover article appeared.

Through it all—through the 1940s and 1950s—it was generally assumed that comics’ readership consisted exclusively of children and illiterate readers. (Though, of course, “illiterate readers” has always been an oxymoron.) Would that readership eventually come together to celebrate comic books as an art form? Nonsense!

But now here we are: April 2014 marks six decades since the Senate heard comics-centric testimony from psychiatrists, publishers, comics creators, and newsdealer representatives. Senators Estes Kefauver (Tennessee Democrat) and Robert C. Hendrickson (New Jersey Republican) had resolved to make “a full and complete study of juvenile delinquency in the United States.” The April 21-22, 1954, hearings included appearances from Fredric Wertham and Entertaining Comics (E.C.) publisher William Gaines. It was at those hearings that years of anti-comics campaigns came together in a series of reports concerning just how damaging comics were.

The snowball throwing begun before World War II was now part of an avalanche, with Wertham actively seeking—and receiving—pre-release publicity for his Seduction of the Innocent. (Mind you, June 25, 1954, Book-of-the-Month Club canceled its contract with Rinehart and Company to offer the book as one of the club’s alternative selections. But that was a minor distraction for those who wanted “crime comics” removed from newsstands, and legislators in several states had already tried to establish laws against the art form.)

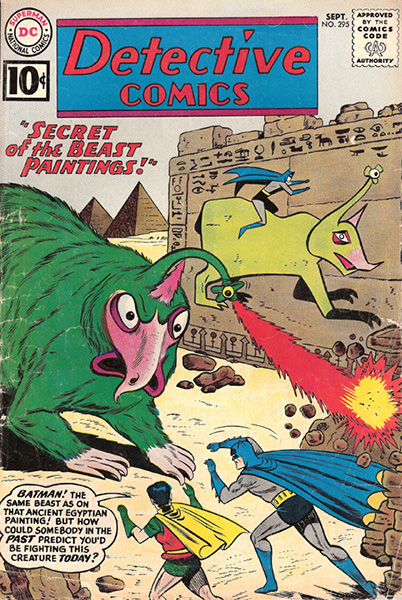

Whew! The story appeared in a comic book titled Detective Comics (#295) but, after seven years of Comics Code scrutiny, the detecting didn’t involve actual crimes.

Whew! The story appeared in a comic book titled Detective Comics (#295) but, after seven years of Comics Code scrutiny, the detecting didn’t involve actual crimes.

TM & © DC Comics

The industry had already tried to protect itself with a code of standards, announced July 1, 1948. The Association of Comic Magazine Publishers had organized the previous year, and its star indicating compliance with those standards soon appeared on participating publications. But horror, crime, and sensational covers were still to be found in the mid-1950s. So comics producers tried again, and 1954 was the year that comic books (which John Mason Brown had called “the bane of the bassinet” in 1948) were, indeed, relegated to the nursery for decades to come. October 26, 1954 saw the Comics Magazine Association of America announcing that it had established new codes, one for editorial content, one for ads. Gone were crooks for Batman to defeat; it was time to replace them with multi-colored aliens.

[By the way—and for the record—Wertham was not satisfied by the removal of horror, crime, and sensational comics. In “It’s Still Murder” (Saturday Review of Literature, April 9, 1955), he complained about even such comic book horrors as all-caps lettering and short line length in word balloons.]

In any case, science fiction-fan convention had long since established a popular culture venue in which amateurs and professionals could meet and exchange views. But it apparently occurred to no one that such a venue would ever be an option for the world of comic books.

But we knew what we wanted, didn’t we? I think those of us reading them in the 1950s had always guessed that comics could provide entertainment for adults as well as for kids. And eventually we established conventions where adults could meet and discuss and buy and sell comic books. And then, yes, then—

Then, slowly, inexorably—it became clear. Comics were for kids, yes. But also for teens. And for adults. And entertainment. And information. In short, the distinctively American art form is now not only acknowledged as a national treasure, but it continues to be the heart of America’s popular culture festival, an annual party in San Diego that began in 1970 and continues today.

The Comics Code has been gone for a few years now. But Comic-Con? It’s bigger than ever. It’s attended by pros and fans, families and historians, all who gather to celebrate the treasures comic book have brought us. I hope I’ll see you there!