Tim Curry remembers the moment he realized that his performance as Dr. Frank-N-Furter in “The Rocky Horror Show,” the London stage precursor to the 1975 cult film, was no longer his alone.

David Bowie and his wife at the time, Angela, were in the audience that night in 1973. Onstage, Frank, the hypersexual alien mad scientist, was being held at ray-gunpoint by his former servants, Riff Raff (Richard O’Brien) and Magenta (Patricia Quinn). They were about to shoot when Ms. Bowie shouted, ‘‘No, don’t do it.” As Mr. Curry recalled by phone from Los Angeles, “That was the first time.”

First a British phenomenon, the sci-fi musical mash-up grew into a trans-Atlantic hit, and later the much better-known feature film with the slightly updated title, “The Rocky Horror Picture Show.” The lines written by Mr. O’Brien, a New Zealand transplant, and those made up on the spot by fans — in some cases, repeated until they became classics — would become inseparable. This symbiosis ensured that “Rocky Horror” has remained perpetually on screens (including a special Halloween outdoor screening at the Hollywood Forever Cemetery in Los Angeles) since it was first released to a nearly empty theater 40 years ago: It is self-updating, never the same sum of dialogue twice, and never, ever dated.

“People still come up with audience participation lines week by week,” said Larry Viezel, a fan who helped produce “Rocky Horror Saved My Life,” a new documentary. “There are lines that are going to be about Donald Trump and the other day there was a line about Cecil the Lion. Whatever is in the news can become an audience participation line.”

Ostensibly the tale of Brad and his fiancée, Janet, a wholesome but stranded couple in Denton, Ohio, who stumble onto the Annual Transylvanian Convention presided over by the “sweet transvestite” Frank, “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” was so much more: a small-scale take on America’s struggle with its conservatism and desires amid the sexual revolution and the glitter-rock era. As Mr. Curry put it, Mr. O’Brien “reached up into the zeitgeist and brought down the most salient ingredients.”

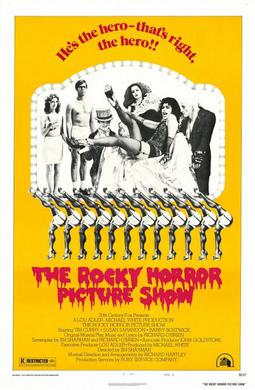

That this strange mix would resonate with moviegoers was never a given. In 1974, the record producer Lou Adler moved the show from London to Hollywood (adding Meat Loaf to the cast). There was also a brief Broadway bid. The show finally returned to a Gothic castle in Britain to become a movie (directed by Jim Sharman, who also directed the stage version) once Mr. Adler cut a deal with 20th Century Fox.

The cast included Barry Bostwick and Susan Sarandon after the studio demanded that Americans play Brad and Janet. But Mr. Curry was allowed to reprise his stage role, complete with leather jacket, fishnets and heels. “He’s the ultimate seducer,” Mr. Curry said of Frank. “Everyone is a potential target.”

Mr. Adler recalled believing in the movie when few else did. Early on, Fox’s European marketing executives were invited to watch the filming of the climactic swimming pool scene. “There was dead silence,” he said. “They didn’t stay for lunch.”

Ms. Sarandon confirmed: “My representatives were so horrified. Nobody else thought it was a good idea.”

After opening in Los Angeles on Sept. 26, 1975 — after a disasterous test screening in Santa Barbara — “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” was scheduled to play Columbus, Ohio, which would have probably guaranteed an early death.

It was doomed from the start,” said Tim Deegan, who worked with Mr. Adler and Fox in what seemed a vain effort to find an audience. John Waters’s lurid, hilarious “Pink Flamingos” was enjoying a successful late-night run at the Nuart Theater in Los Angeles; Mr. Deegan saw a model.

“I was totally convinced there was a midnight audience,” he said.

Fox wanted no part of it, especially when executives saw the promotional poster, which showed a giant pair of lips and the tagline, “A different set of jaws.”

Only the threat of a lawsuit and the support of the studio chief, Alan Ladd Jr., enabled Mr. Deegan to eventually book the film into the Waverly Theater in Greenwich Village in New York during the spring of 1976 — not before Mr. Deegan was fired twice by Fox. Still, the lines grew until fans, in costume and carrying props, had to arrive hours before the midnight screenings.

Mr. Bostwick insisted that, “Besides all the fan participation, if you see it at home quietly and you’re not being yelled at with all the clever retorts, I think you’ll see what a well-made film it is.” But the movie is truly inseparable from the fan imprint, over the years becoming a kind of social network, dating service and, to some, way of life.

“You’re going to find like-minded people,” Mr. Viezel said of the midnight showings. “Even though everyone comes from different walks of life, people who find their way there tend to be social outcasts who form this camaraderie.”

Likening the gatherings to a “Mass,” Susan Sarandon said that “Rocky Horror” was an important film because “it’s given a home to so many people, especially those who need to be accepted for who they are.”

The film’s credentials as a cultural phenomenon have not been in doubt for decades. It figured in the plots of movies from as long ago as 1980 (“Fame”) and as recently as 2012 (“The Perks of Being a Wallflower”); it’s been honored by the Library of Congress; there’s a statue of Mr. O’Brien’s likeness in his native New Zealand; and the film was the subject of its own 2010 “Glee” episode (with cameos by Mr. Bostwick and Meat Loaf). The red-lips logo (they belong to Ms. Quinn) have become a pop icon. “There isn’t anyone who doesn’t see that and doesn’t know what it is,” Ms. Quinn said by phone from Britain.

The film’s box-office status has also long been cemented. With more than $100 million in earnings, “Rocky Horror” plays weekly in about 75 theaters across the country. Those midnight screenings have been credited with keeping many independent movie houses alive. Today the movie’s message of tolerance and shame-free indulgence, along with its gender politics, are more or less mainstream. Its “Don’t dream it, be it” takeaway line is a rallying cry for every self-styled new-media star. So, is it time for humility or a series of victory-lap projects? This seems to be a divisive point among the once close-knit “Rocky” family.

Mr. Adler produced an ill-fated 1981 sequel, “Shock Treatment” (which included Mr. O’Brien, Ms. Campbell and other “Rocky Horror” veterans), but, as he put it, “It couldn’t overcome ‘Rocky Horror’ — the shadow was too long.”

Still, he is developing “The Rocky Horror Picture Show Event,” a television special for Fox, though he is aware of the risk. “We have to do more than just repeat what we did with different people,” he said, adding: “The problem is that we’re not casting the original script. We’re casting Tim Curry.”

Understanding the intricacies of the “Rocky Horror” legacy is a lot more complicated than “The Time Warp” (that’s just a “jump to the left … and then a step to the right”). Fox has long since come around, recently releasing a Blu-ray version. And Mr. Curry, who is recovering from a stroke he had in 2012, was happy to reminisce about his screen creation turning 40. But there was a time when he tried to distance himself from his most famous role because he worried it was holding him back. “I finally sorted through that,” he said. “I realized I’d been lucky. I still feel lucky.”

Over the years, Mr. Adler came to own the music and the film rights, and Mr. O’Brien’s sore feelings have gone public. “There is no incentive for me to further the fortunes of others, consequently you will have to talk to Lou Adler,” he said by email.

When asked about Mr. O’Brien, Mr. Adler went uncharacteristically quiet. “There’s nothing I can say,” he said.

Still, “Rocky Horror” will go on, probably as long as there are theaters with midnight slots, sought out by those chasing the first feeling of being accepted no matter what, as one of its songs goes, or who they are.

Perhaps Mr. Sharman said it best. Declining to give a full interview — “thinking about ‘Rocky Horror’ opens a Pandora’s box,” he said — he sent a thoughtful email that read in part: “On the opening chord on the opening night of the original stage version at the Royal Court an electrical storm broke over London, and that lightning has been chasing it ever since.”

|